On Retractions in Biomedical Literature

Posted on Sat 23 March 2019 in Data Science

The fierce competition in academia and the rush to publish, many times lead to flawed results and conclusions in scientific publications. While some of these are honest mistakes, others are deliberate scientific misconduct. According to one study, 76% of retractions were due to scientific misconduct in papers retracted from a specific journal1. Another study from 2012 found that about 67% of the total retractions can be attributed to misconduct2. Such malpractices demean the fundamental purpose of conducting science- the pursuit of truth. Additionally, such a research is a waste of tax payer’s money. For the authors publication retraction, while just, can have debilitating consequences such as drying up of grant money, vanishing of collaborators and absence of junior colleagues and students to assist in running the lab. Motivated by several retractions in biomedical literature making news, I decided to investigate deeper.

All my analysis is based on data from PubMed, a free search engine of publications in life sciences and biomedical sciences. I collected this data in February 2019 using Eutilities, an API (application programming interface) for accessing National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) databases (this includes PubMed). In this post, I will discuss all the players - authors, journals and countries, which are involved in conducting science, reviewing and publishing science, and funding and supporting science. The PubMed data is likely incomplete as not all information about retracted publications may be recorded on the website but I am assuming that the results will still be statistically valid and will generalize to the real situation.

The rising number of retractions in the biomedical literature

According to the PubMed data there are 6,485 publications retracted as of Feb 5, 2019. While discussing this number with a biologist friend, her first reaction was “Wow! That’s small! I was expecting a larger number”. And she is not alone having such a thought. According to a survey by Nature3 nearly 70% of the surveyed biologists have failed to reproduce someone else’ experiment and according to 50% of these surveyed biologists think that at the most 70% of research is reproducible. According to a recent study published in Molecular and Cellular Biology4, there are around 35,000 papers that are eligible for retraction due to inappropriate image duplication, which is just one of the many reasons for retraction. The other reasons are plagiarism, data fabrication, unreliable data, duplicate publication, no ethical approval, and fake peer review, to name a few. Thus, 6,845 retracted publications may just be the tip of the iceberg.

It is not just recently that we started retracting publications. The first biological paper, which was retracted, (in my dataset) was published in 1959 in Journal of Biophysical and Biochemical Cytology titled ‘On the primary site of nuclear RNA synthesis’. However, the number of retractions per year is increasing. While the retraction rate was 1.8 papers per 10,000 papers published in 2000, it has increased to 4 papers per 10,000 papers published in 2015. This might seem a small number in the first glance but just imagine what havoc a single paper can cause in terms of influencing others’ research, especially when it is claiming to be a breakthrough in the field or if the paper deals with clinical trials or medical treatments. Also, remember that while we are considering only retracted papers, there are likely many other papers that should be retracted but have not been.

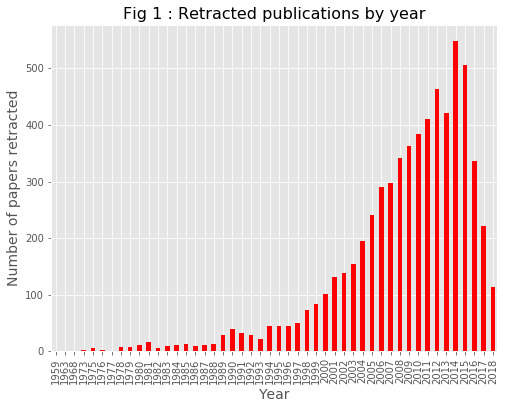

Below is a bar graph showing the number of papers that were published in a given year and retracted later, showing an increasing trend of retraction in science (Fig 1).

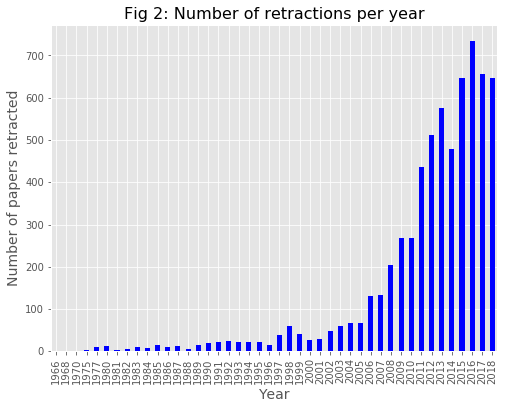

Next, I checked how many publications are retracted in a given year irrespective of their publication year. This showed a sharp increase in number of retractions in mid to late 2000s, with a maximum in recent years. (Fig 2).

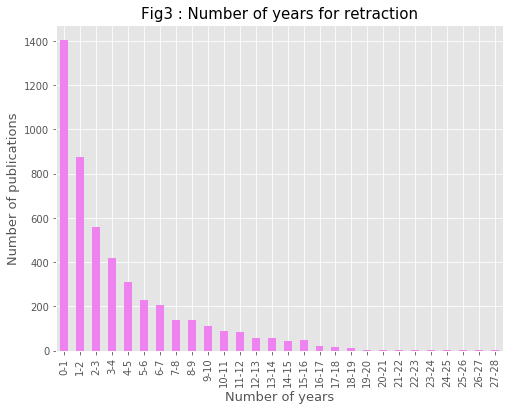

Subtracting the retraction date from the publication date, provided the number of years it took for retraction. As can be seen from the Fig 3 , while maximum retractions happened within a year, it has taken up to 27 year for some (Fig 3). The average duration for retraction is 3.7 years. This explains the less number of retractions seen for the years 2015-2018 in the Fig 1.

Only a few authors are repeat offenders

According to the data, there are 24,722 authors involved in retraction of 6.485 publications. Out of this number 82.7%, that is, 20,448 are one-time offenders, while nearly 4,000 have their names on 2-5 retracted papers. There are 367 authors that have higher number of retractions (more than 6) to their account. Yoshitaka Fujii with 166 retractions in anesthesiology is on the top slot with maximum number of retractions. (Fujii apparently published based on falsified data for nearly two decades. The Wikipedia page cites a reference indicating 183 retractions of Fujii’s publications.) While the low number of repeat offenders is a relief, the fact that biologists with malicious motives were allowed to conduct science for a long time and publish great number of papers, until stopped, is a matter of concern.

| Number of Retractions | Number of Authors |

|---|---|

| 1 | 20,447 |

| 2-5 | 3,908 |

| 6-20 | 345 |

| 21-50 | 18 |

| 50-100 | 3 |

| 101-above | 1 |

Country-wise retractions

To answer this part of analysis, I needed affiliation data. This data was messy with many authors providing only their university or institute names without the country name and many times country names appear in various forms such as UK/United Kingdom/England. To address the first issue I have used SPARQL to obtain data from Wikidata. This gave me a list of 102,958 organizations which included names of various universities, research institutes, engineering colleges, university systems, deemed universities, international organization, hospitals, businesses, research centers, and academy of sciences (possibly, all the places where biomedical research is conducted) across the globe, that assisted in finding the corresponding countries. I used Wikipedia to obtain alternate country names to solve the second problem.

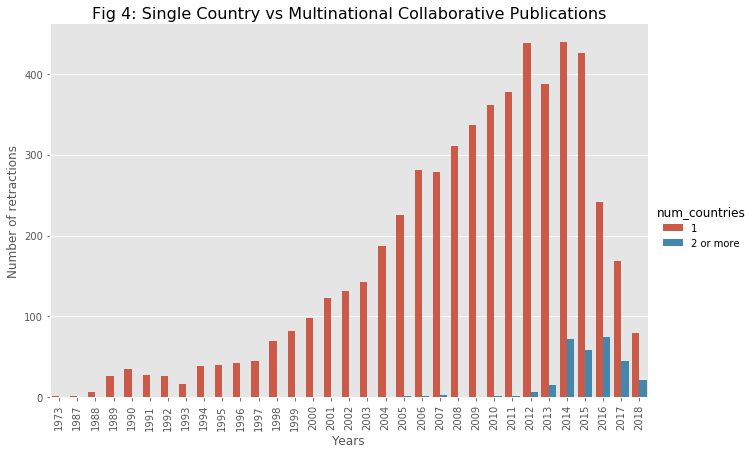

With our current scientific research becoming increasingly collaborative in nature as authors for a single paper can come from different institutions as well as different nations. Therefore, for every publication I have kept unique values for affiliated countries. As can be seen in the figure below, majority of retractions are coming from single countries and retracted papers with international publications started coming up only from 2005 and still make only 4.6% of total retractions.

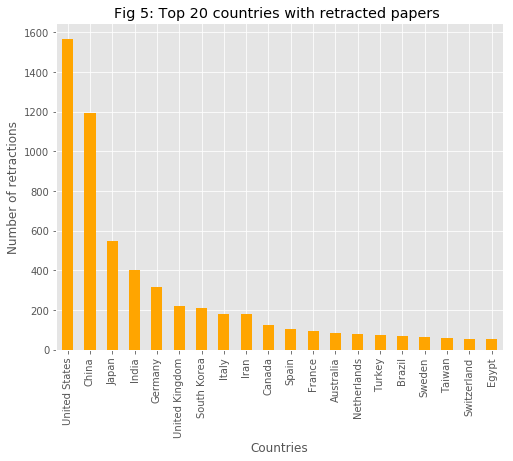

Retracted papers come from 98 countries with United States, China, Japan, India, and Germany occupying the first five ranks (Fig 5).

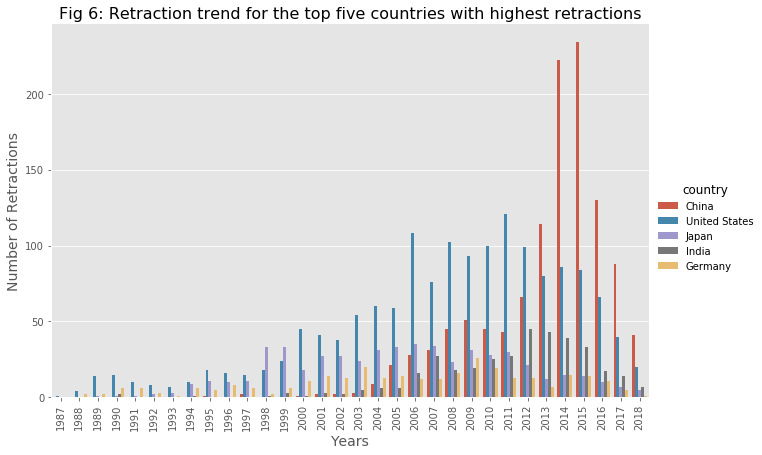

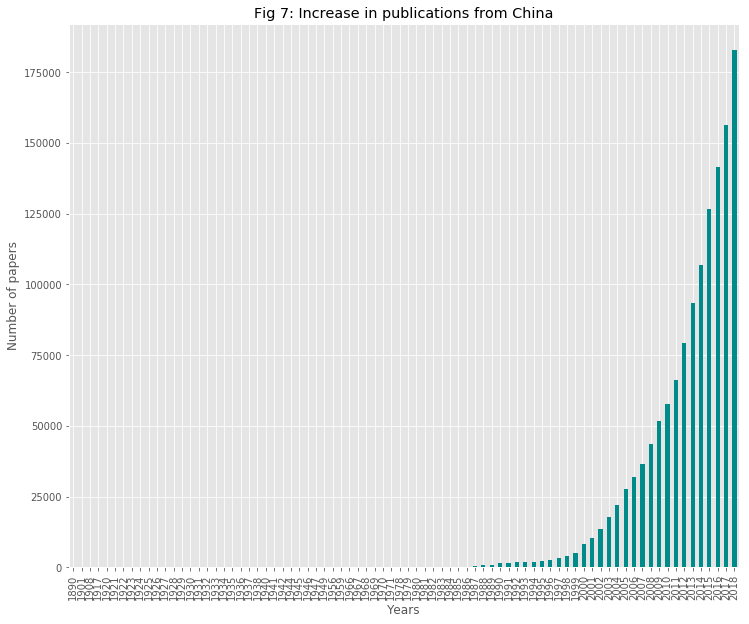

If we zoom into the performance of these 5 countries, we can see a sharp increase in number of papers retracted by China in mid-2010’s (i.e., papers published during that time) (Fig 6) which correlates well with the increasing rate of its publication velocity (Fig 7).

China’s publication rate has soared nearly 15 times from the beginning of this century to 2015. With increase in science funding and a simultaneous increase in competition to publish in journals indexed by Thomson Reuters’ Science Citation Index (SCI), a crucial requirement for promotions and research grants for the Chinese scientists, unethical means to publish in SCI journals have transpired. Such unfair means include buying authorship, self-plagiarizing by publishing English translation of already published papers in Chinese, fake peer review, ghostwriting and buying paper authorships5 6. With this debacle of a sharp increase in number of retractions, in 2017, the Chinese government adopted a zero-tolerance policy to control unethical science. Some of measures include banning the fraudulent researchers from their institutes for various time periods, revoking awards and honors, retrieving research funds, taking down websites advertising selling of papers, and investigating third-party agencies involved in selling papers7 . It remains to be seen if China’s policies will help in reducing the burden of retraction and can therefore be used as a model for other nations.

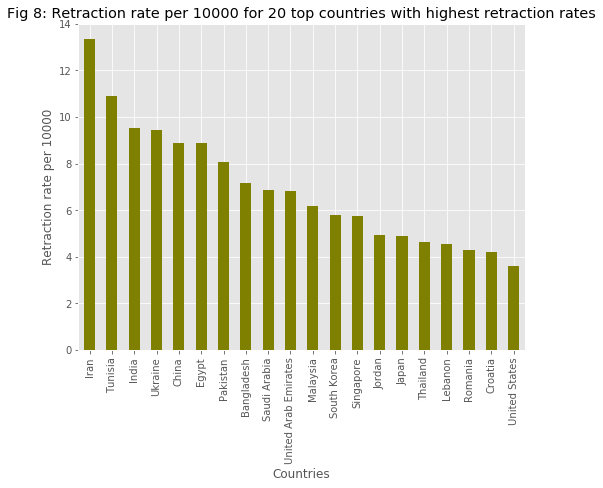

While the above record of country-wise retractions helps us understand which countries have maximum number of retractions, its equally important to check which countries have highest retraction rates (number of retractions per total number of papers published). In this, countries such as Anguilla, Aruba and San Marino occupy first three slots. But, they together have published less than 300 articles and have 1 retraction for each. To avoid getting countries that are not producing many biomedical research articles, I set a threshold of at least 10,000 papers published by any given country. With this we obtained our top players in this slot- Iran, Tunisia, India, Ukraine, and China (Fig 8). According to a 2018 report8, 80% of the retracted papers from Iran were retracted due to scientific misconduct, ringing an alarm to control scientific fraud.

While authors are the key responsible figures in any scientific publication, the publishing journals and editors also have some responsibility in not allowing publication of compromised research or at least actively retracting such publications. This brings me to the next point of retraction in scientific journals.

Most retractions come from low impact factor journals

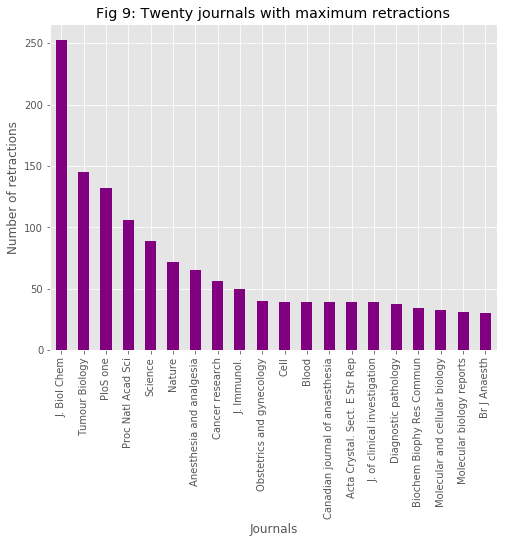

Retracted papers have been published in 1,988 different scientific journals with Journal of biological chemistry, Tumor Biology, Plos One, PNAS and Science occupying the first five slots for highest number of retractions (Fig9).

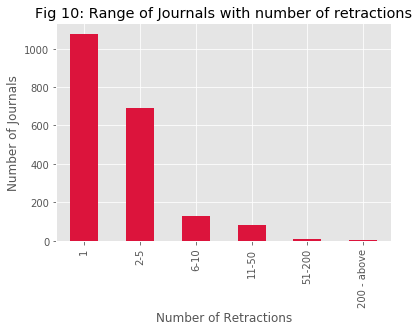

While 54% of these journals are only one-time offenders, journals like Journal of biological chemistry have 253 retractions (about 13% of total retraction) to their credit followed by Tumor Biology with 145 and Plos One with 132 retractions (Fig 10).

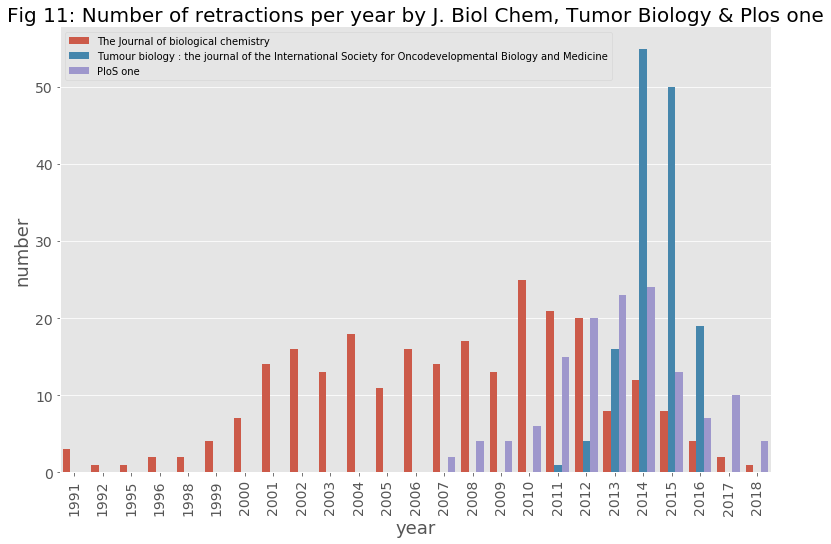

Compared to the rest of the journals with retraction, retractions from Tumor Biology started from 2011 papers and showed a sharp increase for 2014-15 (Fig 11). Following these retractions, over 100 of which were attributed to fake reviews, in July 2017 Web of Science discontinued the coverage of Tumor Biology. This means it has no impact factor since then and most researchers will not be interested in publishing in this journal.

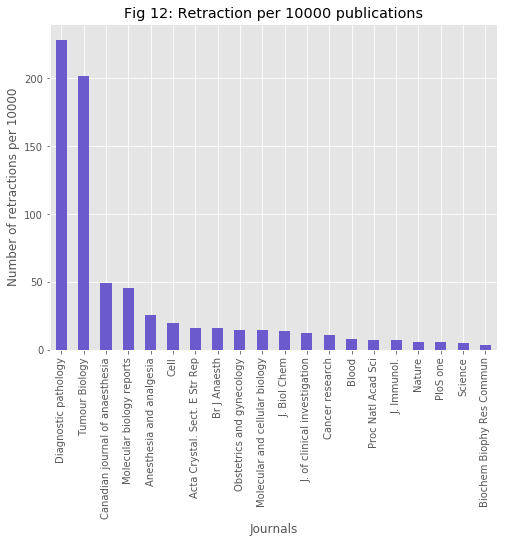

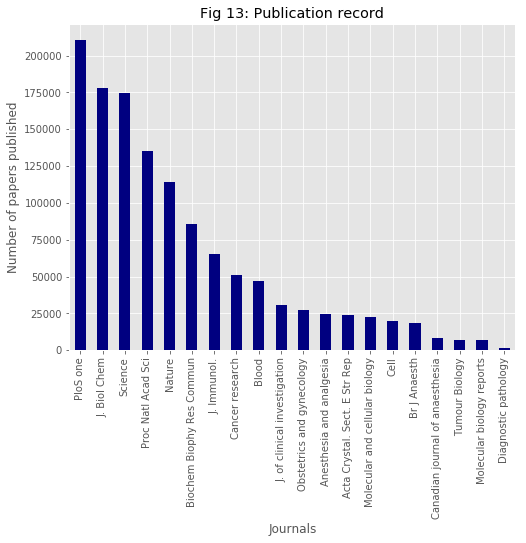

Additionally, out of these top 20 journals, retraction rate (number of retractions per total number of papers published by a journal) is highest for Diagnostic pathology followed by Tumour Biology (Fig 12). But, compared to Tumour Biology, Diagnostic pathology has 4 times less number of publications and nearly 4 times less retractions. On the other hand Plos one, which started fairly recently (2006) compared to the others (except Diagnostic pathology, which also started in 2006), has highest number of publications (Plos one publishes in all areas of science, technology, and medicine but since my data comes from PubMed I am considering only biomedical and lifesciences publications) out of the other 19 journals and has third highest number of retractions (Fig13). If this massive publishing is impacting Plos one’s quality needs to be considered by the publisher.

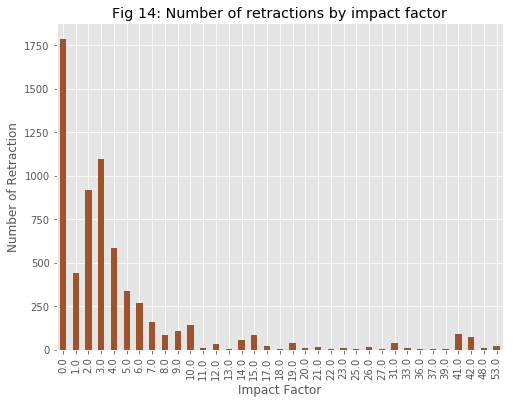

As impact factor of journals is one of the deciding criteria for the researchers while selecting where to publish ones research, I checked if this factor has any link with retractions. For this purpose impact factor listing for the year 2018 issued by Clarivate Analytics was used. The analysis revealed that about 80% of retractions are from journals with 0-5 impact factors. Although, retractions also happen in journals with higher impact factors (with impact factor even up to 53), they are less frequent (Fig 14).

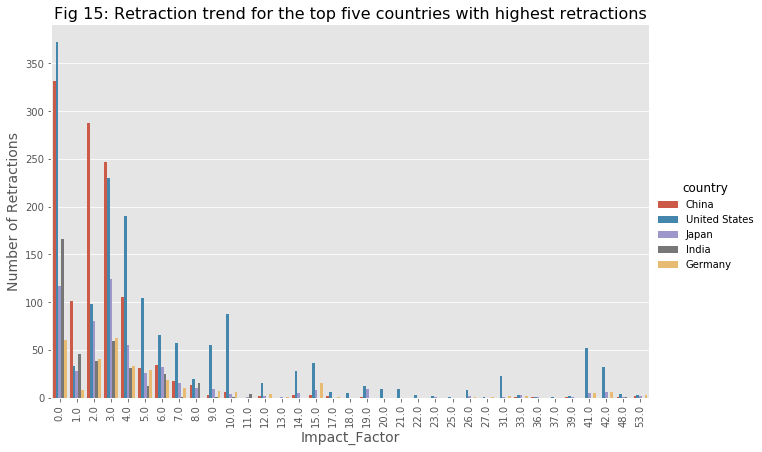

Next, I was curious about how this distribution of retraction looks for the top 5 countries (that also makes 62% of total world’s retractions). As expected most of the retractions from these countries are restricted to lower impact factor journals, but for most of the retractions in higher impact factor journals it is usually coming from the US, and in some cases Japan and Germany (Fig15).

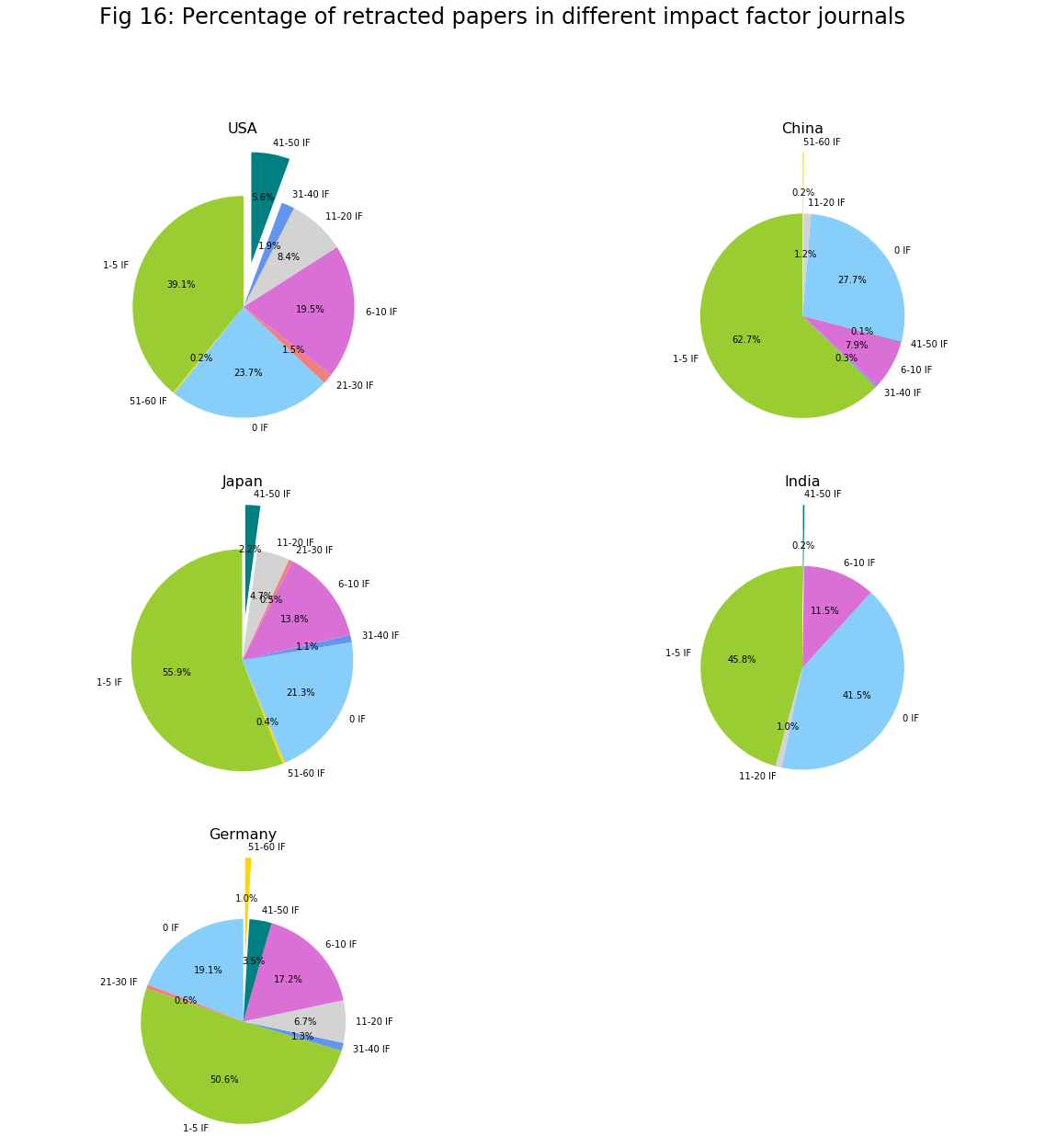

When total number of retractions for each of these countries is studied, its evident that while China and India have up to 90% and 87.3% of their total retractions in low impact factor journals (0-5) respectively, US has only 63%. Japan and Germany also have lower percentage of retractions in low impact factor journals (0-5) compared to India and China. This shows a slight skew of distribution of retracted papers for at least these three developed countries showing more of their retractions in higher impact factor journals compared to the two developing countries, China and India (Fig 16). In a 2012 study2, most retractions due to fraud have been reported from US, Japan and Germany and correlates with higher impact factors. In addition, the authors found that retractions due to plagiarism and duplication happen more in China and India and involve low impact factor journals. This should be investigated further. I have not found comprehensive data on reasons for retractions but would love to dig in if something becomes available.

Conclusion

So far we have seen how number of retractions has increased over the years, authors, countries and journals with highest retractions. While ‘publish or perish’ is not an optimum situation to conduct research in, dishonest science is surely not an answer to it. It not only affects the authors of a retracted publication but can also direct other scientists towards an unproductive direction of research and in worst scenario can lead to inappropriate medical treatment of patients. Moreover, all this decreases public trust in science. While retraction exposes the dark side of science, the positive side of stamping out bad science is that scientists and others involved in this field are willing to correct their mistakes and maintain its sanctity.

If you are interested in acquiring the data used here or in checking the source code of this analysis, please see my Github repository. If you have any suggestions, please do not hesitate to contact me at my email.

-

Moylan, E.C. and Kowalczuk, M.K., 2016. Why articles are retracted: a retrospective cross-sectional study of retraction notices at BioMed Central. BMJ open, 6(11), p.e012047. ↩

-

Fang, F.C., Steen, R.G. and Casadevall, A., 2012. Misconduct accounts for the majority of retracted scientific publications. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(42), pp.17028-17033. ↩↩

-

Baker, M., 2016. 1,500 scientists lift the lid on reproducibility. Nature News, 533(7604), p.452. ↩

-

Bik, E.M., Fang, F.C., Kullas, A.L., Davis, R.J. and Casadevall, A., 2018. Analysis and correction of inappropriate image duplication: the molecular and cellular biology experience. Molecular and cellular biology, 38(20), pp.e00309-18. ↩

-

Hvistendahl, M., 2013. China’s publication bazaar. ↩

-

Liao, Q.J., Zhang, Y.Y., Fan, Y.C., Zheng, M.H., Bai, Y., Eslick, G.D., He, X.X., Zhang, S.B., Xia, H.H.X. and He, H., 2018. Perceptions of Chinese biomedical researchers towards academic misconduct: a comparison between 2015 and 2010. Science and engineering ethics, pp.1-17. ↩

-

http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2017-07/28/c_136480677.htm ↩

-

Masoomi, R. and Amanollahi, A., 2018. Why Iranian Biomedical Articles Are Retracted?. The Journal of Medical Education and Development, 13(2), pp.87-100. ↩